Edith Turner Wilson (née Paynter)

1889 - 1982

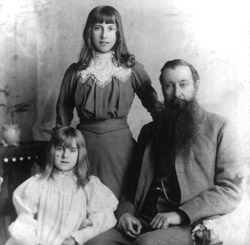

Left to Right: Robert (Bertie) MacNaire Wilson,

Doris Wilson, Willie Mitchell Turner Wilson, Edith Paynter

Left to Right: Robert (Bertie) MacNaire Wilson,

Doris Wilson, Willie Mitchell Turner Wilson, Edith Paynter

Ian Caldwell writes: "I think the photograph

of the Wilson brothers and my grandmother, etc,

was taken at Robert McNair Wilson's wedding to Winnie, which would be about

1908.

From my father's Reminiscences:"Married

brother-in-law Dr Willie Turner Wilson; lived in Wembley till she died there in

1982 - to me the best known of them all".

And from my own recollections: A lovely lady who I remember visiting at

her home outside London (in Wembley, I guess) in the 1950s. Sadly we didn't visit

her in later years. My sister and I share fond memories of her.

s

Outline her Life

From Ian Caldwell: "married in 1913 to Dr.William Mitchell Turner

Wilson (1882-1955), whose brother, Dr.Robert McNair Wilson (Bertie) had married

Edith's sister, Winifred (Winnie). The two

brothers, both medical doctors, were good friends. Both had qualified at Glasgow

University. At first William practiced as a GP in Scotland and was working at

Arrochar, Loch Long, when their first child, Helen, was born. Then William decided

to follow his brother and move down to London where a better living could be

made, so their next child, Ian Henry Turner, was born while they were living

in Golders Green. Their last child, Elizabeth Margaret, was born while they

lived at Hendon, and they eventually settled at Rhonallea, 351 Harrow Road,

Sudbury, Middlesex".

Ian Caldwell's further notes: Edith May Paynter, my grandmother, was

born in 1889. She enjoyed her childhood in Alnwick and went to Newcastle Art

College. In 1913 she married Dr.William Mitchell Turner Wilson, a G.P. who was

practising at Arrochar, Loch Long, which is where my mother, Helen Turner Wilson,

was born. The family came down to London where Willie's brother, Bertie, was

working as Medical Correspondent for the Times Newspaper, and Willie went on

to establish a large general practice in the Harrow area and was also the doctor

for the Sandersons Wallpaper factory at Perivale, Middlesex.

When he was young William was a tall, dark-haired man with strong features.

He was born in Glasgow, the son of a sugar broker and he and his brother, Bertie,

studied medicine at Glasgow University. He went to Egypt during the First World

War and when he returned he had put on weight and had lost much of his hair.

Edith was very fond of him. They had three children:

Helen Turner Wilson, (b.18/7/1914) who married John Thomas Caldwell, (26/12/1901-26/12/1970)

an Australian engineer, who had been married previously to Constance Hollitt

by who he had three children: Joan Constance Caldwell, Frederick John Caldwell

, and Elizabeth Mary Caldwell. These three all married and had children.

With Helen John Caldwell had two more children, Ian William Robert Caldwell, (the writer

of this family history), and Catherine Caldwell, both of whom have married and

had children as below.

Ian William Robert Caldwell,

son of John and Helen, was born on 22nd July 1942 married (1) Anna Jadwiga

Zofia Korzen, b.15/3/44 by who he had three children, Anthony Mark b.21/10/63,

Sasha Karen Caldwell, alias French b. 31/7/65, and Jonathan Stephen Tristram

Caldwell alias French, b.10/12/67, married (2) Gabrielle MacPhedran, b.13/10/41,

by whom he had three children, Christopher Edward b.15/11/72; Toby John b.16/5/74;

and Nemone Catherine b.19/9/77; and married (3) Gillian Candlish Willment,

nee Tribe, b. 5/4/39 by whom he had two step children, Victoria Ruth Willment

b.1/1/68; and James Thornton Robert Willment b.25/3/72.

And now a new generation have started to arrive, Jonathan has married Candace

Fleming and they have Arran Fleming, (6/3/97), Francis Bruno(12/1/99) and

Lucian Fleming (b.30/6/2000), and Toby married Lisette Cohen and they have

a daughter, Lila May Caldwell,(b.26/3/99); and James and Nicole Katerina Zach

have a daughter, Yasmine Aisha born 2/2/2000. The last arrival is Archibald

Jerome Doidy Caldwell, born 30/9/02, is the son of Christopher Edward and

his partner, Delphine Doidy, a French girl from Nantes, and they live in Barcelona.

Catherine Caldwell (b.4/11/45) daughter of John and Helen. Catherine married

Richard Walsh Cuff (b.22.12.41)and they had two children Zoe (b.12/8/66) and

Julia, (b.4/9/67) born in England. They emigrated to Australia where a third

child, Robert, was born (b.19/3/72).

Zoe Cuff married Robert Panetta on 11.9.94 and they have three children,

Matthew Panetta (b.30.6.96), Timothy (b.29.12.97) and Tessa Panetta (b.15.7.02).

Julia Cuff married Tudor Robertson has two children, Jodi Robertson (b.17.1.1991)

and Charlie Robertson (b.25.5.1994).

Robert John Walsh Cuff (b.9.3.72) married Denise Kennedy (b.9.7.65) and they

have a son, Macarthur Cuff (b.9.8.01).

Edith and Willie's second child was Dr.Ian

Henry Turner Wilson (b.13.6.1917, d. 2007), a Doctor of Medicine like his

father, who joined him in the practice, then married Elizabeth Mary Caldwell

(b.5/3/1932), his brother-in-law's daughter. The family emigrated to Australia

in 1964.

The last child of Edith and William was Elizabeth

Margaret Ross (b.29/7/1920) who studied Economics at the L.S.E. and married

her wartime boss Alfred William Ross a research scientist working on the development

of radar during the Second World War, with a double first from Cambridge in

Physics and Chemistry, and they had three daughters: Carol Elizabeth Ross (b.27/11/46),

Vivien Louise Ross (b.6/10/50) and Gillian Roberta Ross (b.29/12/51), who all

married and Carol Elizabeth and Vivien have children.

Carol Elizabeth Ross studied medicine at Guys where she met and married Sean

McAuliffe a fellow student and they had a son James (b.2/6/75) who is a fisherman

with his own boat and a daughter, Joanna Mary (b.15/5/73) who is a qualified

nurse. Joanna married Howard Hurd and they have four children, Joseph Samuel

(b.23/12/98), Daniel Alexander (b.14/9/2001), and twin girls Rosie and Zoe

(b.4/6/2003), .

Vivien became a school teacher and married Nicholas Young a fellow teacher

and now a headmaster, and they have three children, Benjamin (b.30/9/75) who

did a degree in Fine Arts at Goldsmiths, Maria (b.28.11/76) who has double

first in English and Art History at Exeter and Christopher (b.24/12/79) who

studied Sound Engineering at Brtistol.

and Roberta married Karl Pomberger who is an Austrian and they live in Vienna,

but have since divorced, though Roberta, (Bobby), continues to live in Vienna.

Below is a copy of a lovely description of life at Freelands as written by

Edith in 1974: [Note: some of the locations mentioned in her text can be

found on the maps included on the Freelands webpage]

SUMMER - AUGUST 1974

My family has often asked me what it was like when I was young. Now I am 85,

and as they are all away, I think I will jot down a few notes for my own pleasure.

I was born the last but one of a family of 12. I think we would have been described

as upper middle class. My father was a solicitor, and my Mother's father was

also solicitor who had offices in London at 1 Clement's Inn, overlooking the

Mansion House. It had a beautiful view of the Lord Mayor's show which I used

to take my children to see from the office windows.

My grandfather was a wealthy man, and had a

large house at Yeovil in Somerset, with offices attached, and I remember the

office flat at Clement's Inn, with the names of Newman (my Grandfather), Paynter

(my Father*), Gould and Newman, my cousin. [* Note: there

used to be much confusion about the Paynter connection with Henry Newman's law

firm. In fact it was Edith's uncle James

Bernard Paynter who became a partner (in 1883) and eventually senior partner.

Her father Henry was never a partner in the firm. See the Law

Firm page for a full account of the firm's history.]

My father who came from Penzance,

Cornwall, was the son of a clergyman and schoolmaster. [In fact his father

Francis was a slightly disreputable lawyer!]

He owned a house called Clarence House,

or Boskenna, I never quite understood which. He was the youngest but one; he

had seven brothers, but no sisters, and they mostly took up Army life, or the

Church, or were solicitors. My Mother also had seven or eight brothers, and

was the only girl; and was married to my father when she was 17 at Hanover Square

Church, London; my father was only 20.

They were set up at Alnwick, a lovely little town in Northumberland, and given

a house in lovely grounds just outside Alnwick, and he was made a partner to

an old solicitor called William Foster. After Foster died, he carried on himself,

and then later took his brother John De Cambourne Paynter as chief clerk; he

was a very handsome man over 6ft tall, and had been a playboy at Oxford University,

and never passed his finals. My Father was 6ft 3'', and they both had long flowing

beards, people used to say they looked like Vikings as they walked together.

Freelands was the name of our house. It was well named as my father and mother

never seemed to be without company, relations or friends were always with us;

and my mother had children so quickly: about 5 in the first 8 years. I don't

think she was particularly fond of children, but was well enough off to keep

a nanny, and a nursery at the back of the house. As the family grew, the house

grew; a large wing was built on at the back, a stairway up to the maid's quarters,

3 bedrooms they had. Later on more rooms were added, and another stairway down

to the kitchen, and a long passage with bedrooms leading to the corridor. Later

this made lovely escapes for 'hide-and-seek'. I remember how the gas jets, I

suppose, made a high pitched noise as you went down the back stair, only lit

by one gas jet that blazed blue in the middle, and forked upwards at the sides.

My Mother was a very good horsewoman, and used to ride in Hyde Park. When she

was a girl she lived in a house overlooking Hyde Park; that was before she was

married, but after that Mother was always adding to the size of her family.

Katie, I believe she was christened Katherine Charlotte, was the first child,

then Ernest. Fred soon followed, then William who was drowned going around the

Cape of Good Hope in the Merchant Navy; the boat was called "The Conway";

this was before I was born. Then my sisters Lily, Eva and Winnie next, then

my brother Edwin Coleman, then Violet, Rose, myself Edith, and the youngest,

Olive. She and I are the only ones now living.

We had a large staff of maids, cook, scullery maid, nurse, and maid general,

groom, gardener, and then a boy. We kept 4 or 5 horses, a cow, pigs, hens, ducks,

two shooting dogs, and Mother always had 2 or 3 little dogs. We had heaps of

stray cats who lived in out-houses; I also remember a monkey, goats, owls, donkey,

goose, and a gander. The gander was a wonderful watch-gander as good as any

dog. There were squirrels, rabbits, guinea pigs, ferrets, and I'm sure far more.

My family would visit all the big houses; they all seemed to have the same

style of living. Any newcomer would be visited, and calling cards left. I think

it was 2 printed cards for the man of the house, and one for the lady, carried

in silver card cases and left on a tray in the hall. Being one of the young

ones of the family I did not do much of this. I was very shy and plain, and

enjoyed playing games, or playing with the animals, or watching things grow.

I used to field at tennis parties all afternoon in order to be allowed to play

a game after friends had left. We had a lovely shady tennis court, with a large

mowing machine drawn by a pony with leather shoes on, like a small elephant

foot in shape, and a stone roller you sat on, as it had shafts and went round

and round the count. I loved this.

My Father was very keen on bird life and nature. On Sunday afternoons he would

walk about a mile to get to the river Alan, and walk along its banks spotting

birds, and nests, and trout and otters, moorhens and water-rats. I often used

to go with him. He loved the song of birds and knew them all. We used to go

to the woods called Callusaes, and had to walk through a market garden. I can

smell the strawberries on a hot summer's day, but I was never allowed to eat

one. There was a small stream running through the woods, and after the bright

sunlight it was shadowy and dark, and then light through an open space of trees.

Sometimes a pheasant would fly with a thundering noise of wings, calling as

it went.

Every Sunday my Father would walk to a little church about 3½ miles

away and read the lessons. We would pass on the way his gamekeeper's house;

a tiny pillbox of a house. The keeper, called Hudson was a huge bully of a man

who kept his family in fear of him; also this big black dog he kept to watch

the woods at night for poachers. This only thing that Hudson was frightened

of was his wee wife; she could dress him down. I don't know how she dared, but

he just slunk away. He, Hudson, had a huge family, and as children, at Christmas

we had to give them some of our toys.

We were not allowed to use the horses on Sunday; and the maids had Sunday evening

off, putting roast potatoes in the oven, and for Sunday night's supper it was

generally cold game, ham, and roast potatoes with butter, and tea or coffee

afterwards in the drawing room.

My Father had a study or smoking room where he retired to, it was an interesting

room with a large glass fronted gun cupboard, nature books, poetry books, Joricks,

bound "Leisure Hours ", "Punch" and others. Under these

were fitted little drawers with rare birds eggs. He never took more than one;

these he blew, and they rested with their names on cotton wool. He had a cabinet

of butterflies: a lovely collection. There were fishing rods and tackle, two

comfortable arm chairs beside a glowing fire, a sofa with a sealskin rug on

it, a copper coal-scuttle, painted window shutters, which were always closed

at night (well made folding shutters with an iron clamp across them). There

were wooden shutters in nearly all the windows which were not noticed until

closed, and there were thick red curtains in Father's study.

He had a lovely reading voice, and used to read out loud for hours on Sunday

at home, generally finishing up with poetry. I used to play clock golf, or bowls

with him after tea on weekdays, and used to make up the 4th at whist for him

when he had men friends in. I knew his play, and if we won I would get 6d. He

never started a rubber after 10 o'clock at night.

Alnwick was I suppose a snobby place to live in. It never troubled me; it was

such a lovely little town with moors just above it, and the sea only about 6

miles away, lovely parks belonging to the Duke of Northumberland who lived in

Alnwick Castle. We were given the key, and could drive anywhere in the park.

Hullen Abbey was a lovely old ruined Abbey where the monks had lived: this was

a favourite picnic spot. We used to have 2 or 3 carriages full and go there

and play hide-and-seek in the ruins. There was a long line of stables we put

the horses in, and a caretaker used to boil kettles for us, and we used the

trestle tables and forms, and brought our own picnic. It was usually where we

went on my birthday, and Howick rocks for my sister Rose's birthday. My mother

always packed the picnic box. She had one of her own designs made: it was a

wooden box, about 2½ feet long, 2 feet high, and it had hinges so it

let down and everything was easy to get at; also if on sands it kept the sand

out. She also invented a metal box that had metal drawers to take on shooting

picnics to keep the stews piping hot. My father rented grouse moor belonging

to the Duke, and also the Callusaes for game and rabbits. He was a wonderful

shot, and had shooting parties on Wednesday half-holidays, and we used to take

luncheon out to the guns. Always on Aug 12th we had a grouse shooting party;

I have a lot of photos of them.

There were no motor cars then, and I remember rushing out to the road expecting

to see my first car, only to find a road traction engine. Roads were rough in

those days. Men were employed to break stones at the sides of the roadside with

long hammers; they were flint, and very hard. These stones were thrown on to

the road an a traction engine used to go over and over them, and some earth

thrown on sometimes to fill up the gaps. Then came the tar mixture, and in summer

it stayed hot and runny. Hedge cutters used to cut the hedges each side of the

road with a long wooden handle and a metal cutter at the end. It was quite an

art to cut and lay a fence, as the branches used to be half cut through and

bent, making it very strong. But for cyclists it was cruel as the thorns were

lying about just ready to puncture your tyres, so you used to have to lift up

your bicycle and carry it along till the road was clear. Some roads never had

anything done to them, and just got worn down by the horse and cart traffic.

I can just remember solid tyre cycles, and a cycle called a penny-farthing.

It had a very small wheel and a large one, and a seat high up off the ground,

very difficult to get on and off, a wall or something high was the best way

to reach the seat.

People in those days were very superstitious, and my mother would not have

may or peacock feathers in the house. She went once to a private house selling

furniture, where there was a very beautiful fire-screen made of steel in the

shape of a peacock with a spread of tail feathers. My mother bid for it and

got it, and someone said to her "peacocks bring bad luck". A few days

after this my elder brother who had a penny-farthing cycle asked my father to

come and watch him rid down a hill near the house. My brother went straight

into the ditch and was carried home unconscious. After a few hours he recovered,

but my Mother got rid of the fire-screen at once.

Funerals in those days were very solemn occasions; six or four black Flemish

horses with long manes and flowing tails and small head on very arched necks,

all beautifully matched. On the top of the horses were the biggest black ostrich

plumes, these stood upright and swayed about as the horses moved. As far as

I remember they were in groups of three: that would be about 18 or 20 plumes.

For a child's funeral these plumes were white. Men wore black crepe swathed

around their top hats. One of our nurse's favourite walks was to take us small

ones to the cemetery where we were allowed to walk around the paths while she

enjoyed a chat with the caretakers wife who had a cottage just within the grounds.

We were safe there, she thought, and so long as we did not make much noise we

were allowed to roam over paths and graves. Everyone going to a funeral wore

black. Men had to have black gloves and tailcoats if they had them. Poor people

and very old people thought it would be a disgrace to be buried in a pauper's

grave, and I remember our old groom whose mother lived with him in a house built

over our stable, paying up 3d a week for her burial. She had a box kept with

a pair of white stockings and nightdress ready for the day. The funny thing

is I never remember her dying.

Our winters seemed to start early and go on for a long time. Very often deep

snow and hard frosts. The Alan River used to get frozen and everyone would go

skating. We had a big drawer filled with all kinds of skates, starting with

the kind with a wooden sole with a screw in the heel which went into a hole

in the heel of the boot, and a strap over the toe. These were very difficult

to keep on. I never had skates and boots to fit or my ankles were very weak,

as I seemed to be skating or walking on my ankles. I was no good at all and

fell most of the time. We had a chair with iron runners and someone could push

you along. This was fun. Things like dustbins used to be set up and roasted

chestnuts were very welcome as hand-warmers as well as eats. Some of my sisters

had Acme skates, these were considered very superior. The place where the Alan

froze first was in the pastures just below Alnwick Castle: a place called the

Lion Bridge, close-by where the road was. The 'Percy Lion' was standing on the

bridge, a lion carved in stone. We had a small sleigh for a pony to draw. This

had one seat for the driver and a place for standing up at the back. When going

down hill this person had to drag his feet to stop it going on to the pony as

there were no shafts. But my Father had a large sleigh, red and black, with

shafts and brakes and silver harness with bells on; it also had standing room

for several at the back. When going up hills the standers had to get off and

half run and walk to keep up with the horse. This was fun. Our groom had a fawn

livery over-coat with silver buttons with our crest on and he wore a top hat.

His name was Tommy Train. He was with us for 20 years and was a great favourite

with us all. If you asked him how old he was, it was always 25.

My Father was a great naturalist and kept a note book in which he always jotted

down the first migrant bird he saw, the date, and where it was first seen. He

was often consulted by naturalists and had great friends through this. Cherry

Kearton and his brother used to stay with us. He wrote books about birds and

gave us one or two. He was a Yorkshireman and came over to the Farne Islands.

Sir Edward Grey was also fond of wildlife, and Lord Armstrong who had a wonderful

house called Cragside on the Rothbury Road. My father often brought clients

up for luncheon; all kinds of people. I remember as a child being so surprised

when my father addressed a Bishop as "My Lord". I never asked why.

In those days when young you did not ask questions. I also remember an old farmer

who took snuff and used a red pocket-handkerchief. He handed out to us children

a packet of boiled sweets he called poison bullets; I never liked them, or him.

I remember the streets in Alnwick being lit by a man with a long pole with

which he lit the street lamp, how I don't know. He started just before dusk.

And in winter a man with a tray carried on his head full of muffins, ringing

the hand bell as he went along. Also a bell was used to shout out any big events

of the day. I remember the man who used to come around with a large musical

box, sometimes on wheels and sometimes only on a small pole, and a poor shivering

monkey dressed in a little jacket and cap who would present a thin cup for coppers

and would perhaps touch his cap. People, I think, felt sorry for the poor little

monkey so generally gave a copper. Then a man with a dancing bear would appear

in the streets, the man sometimes played a mouth organ and made the poor smelly

bear get up on its hind legs and shuffle about. Sometimes it had a halter on

and sometimes a chain and ring in its nose. They were generally big black bears

standing up as tall or taller than the man. I believe he used to sleep with

his bear in any place he could get shelter. Sometimes a gypsy woman would come

around with a cage of budgies and for a coin would pull open a drawer with folded

coloured papers and the budgie would pull out one of these papers which your

fortune was printed on.

One of the yearly events was the Church Teas. These were held in a church hall,

long trestle tables with white cloths on and long forms for coats and a table

groaning with scones, teacakes, sliced currant cake and small cakes and a huge

tea urn at either end. I think Sunday school children had free teas and a very

small charge, if any, for parents; and they sat and drank tea, as much as they

liked. Then there was a concert or magic lantern show. I remember a slide that

had a man's race with his mouth wide open and a stream of rats which, one after

another, disappeared down his throat. I think it was done with a revolving wheel,

with pictures of rats on it that made the picture on the screen look as though

he swallowed them. Then when the children and the elderly went home, the place

was cleared for a dance.

Christmas was a wonderful time for us children; my Mother enjoyed it too. She

planned everything so well. About a week before Christmas, Tommy Train took

our horse and cart out to the Callusaes (woods) and brought back a load of holly

and the time for decorating was at hand. The family sat down in a large empty

room, with a huge fire burning logs in an open fireplace, with a chimney place

in which you could stand up in on either side. We had large clothes-baskets,

balls of string, big needles, and scissors to cut the leaves off the stems into

the clothes-baskets; then we had to thread the leaves on to the string making

long ropes of green. These decorated the staircase and hung in loops on the

dining-room walls. Mother kept wooden frames about 2 feet wide and 6 feet long

covered with turkey-red cotton with large white cardboard letters sewn on saying

"Welcome Home ", "Happy Christmas to All". These frames

were kept down in the cellar and were brought up for Christmas.

The cellar was a very large one with a part boarded off for potatoes. Then

there was a part entered by a locked door, with latticed shelves with a large

quantity of vintage wines. My Father knew them all and would bring out the bottles

he thought best for the occasion, such as dinner parties, Christmas and weddings.

We always had whisky, port or claret at dinner and always dressed for dinner.

A barrel of beer was kept in a large cupboard outside Father's study, (smoking-room)

and people could help themselves. In spite of all this none of us later in life

took to drink.

Santa Claus visited us all, and, on Christmas morning we children, dressed

in dressing-gowns and eiderdowns, collected together and sang carols outside

my parents' door and woke them up and carried in our Santa Claus stockings.

Father said little, but Mother was most appreciative. After breakfast we all

went to church, and after lunch, generally some went for a walk. In the evening

we all dressed for dinner, to which my Uncle john and his sons always came.

About 20 or more sat at table. Mother generally had a roast goose to carve,

and Father, a huge turkey. Turkeys in those days had a high pointed roast bone,

which always as a child reminded me of my sister Lily's nose, politely called

a Roman nose. Now turkeys are flat and rounded; how fashions change. We had

a wooden train engine with trucks, and all our presents which came by post were

stacked on this train, and Christmas cards as well, and at dessert time Father

pulled this train up the table to him and distributed our letters, cards and

gifts. One Christmas we had General Booth's nephew with us for dinner; he wanted

parcels too. After dinner, snap dragon (raisins set on fire with whisky or brandy)

and fished out by fingers. Later we all adjourned to the smoking room, where

we roasted chestnuts on the open hearth, and my father read a ghost story previously

selected by him. (He read aloud beautifully), and often when he just got to

an exciting part a chestnut would pop and fly across the room, a scramble to

get it rather upset the story. What a happy time we had.

On New Year's Day the hounds met at our house. The Duke of Northumberland had

a pack of foxhounds, and they met at the field at the side of our house. It

was generally a big hunt, and huntsmen in their pink coat came from quite a

long way off. Our maids would take around drinks to the huntsmen. It really

was a lovely sight. Two of my sisters rode two hounds every week if the meet

was not too far away. They used to take plain chocolate and raisins and a flask

of brandy, I suppose it might be. This was in case of accidents or cold. There

were the Percy hounds, and the other pack was the Warkworth hounds. The Creswells

and Alec Brown of Calley Castle also had hounds. Beagles were brought by Cambridge

students later on, to hunt hares. We used to follow them on foot, and get to

a hill or high spot to view them. Glanton, a small village about 9 miles away

had lovely country for beagles. The otter hounds used to be brought to hunt

the river Alan. My Uncle John Paynter used to wear the light blue jacket and

red tie, and I expect he was something to do with the hunt. A well known picture

in oils, I remember, with my Uncle in a prominent position in the river, with

men with poles in their hands, and hounds swimming around and sniffing the banks

of the river. This was a really pretty sight, and as the otters nearly always

got away, it did not seem too cruel.

My father had a half share in Shilbottle pit, and Uncle John and Nat Dunn had

the other half. My father seemed to have all the work to do. He chose a pit

manager and used to visit the pit every week to see to the books and complaints.

He used to visit the sick, or hard cases, and was well liked I think. I never

liked Shilbottle and hated sitting in the dog-cart waiting for Father to finish

work. The pit machinery made pumping noises, and then the sirens would blow

loudly, and the horses were frightened, and would prick their ears up and quiver

all over; the pit yard was small and I felt how horrid it would be if I lost

control. On Sundays Father walked 3½ miles to Shilbottle Church; I often

went with him, and he read the lessons. I remember three different vicars: I

could write yards about them. We used to call and see Hudson the gamekeeper

on our way home.

Every winter there was a concert in the village hall, lit by gas. There were

trestles for seats. One family called Young had a very good voice, and used

to sing "Excelsior", or "In a Monastery Garden". My sister

Rose had a good voice too; I remember her singing at this concert, a duet, with

a little man who worked in Hardy's fishing shop. He was small with weak blue

eyes, and a very waxed moustache. They sang, "Oh That We Two Were Maying".

It struck me as so funny, I never heard of anyone going maying, and I don't

think I ever asked or mentioned it. Sometimes they would have a small play,

and my eldest sister Katie would paint the scenery for the background.

When any of us got married, the pitmen subscribed and gave us a lovely wedding

present. I remember my sister Winnie getting a large silver tray. I got a silver

soup tureen with an inscription from Shilbottle engraved on it.

The pitmen loved their greyhounds and pigeons and rifle range. One pitman was

Grace Darling's nephew, more about him later.

For about 2 months every summer we rented a furnished house on the coast about

16 miles from Alnwick. This house was called Monk's House, and was built just

off the road half way between Seahouses and Bamburgh. The Farne Islands are

about 3 miles out at sea. At night I used to watch the Farne lighthouse men,

and a small church, and the ruins of a small castle on the largest island. Then

further out was the Longstone Lighthouse and the Brownsmen: this had only a

lighthouse cottage. The lights were lit by oil, and on the inner Farne a donkey

was kept to pull up the barrels of oil for the lighthouse. When the new lighting

system came the donkey was not needed, and luckily for the donkey we were visiting

the island. My mother overheard the fishermen saying they were getting rid of

the donkey: they were going to throw him over the cliff. My mother said "Do

no such thing, I will give him a home", so the donkeys legs were tied,

and he was put in the boat, and brought to shore, and lived and died after many

years at Freelands. He used to pull the roller for the tennis court, and give

rides to children. And a donkey in the field seems to make horses stay there,

this is well known. This donkey loved to chew tobacco, and would drink beer

if the bottle was held for him.

My father used to choose to take bird watchers over to the islands at breeding

times. Steam tugs used to take visitors over for a day trip to the islands and

the steamer used to blow it's siren just when passing the pinnacles which were

covered with gillemots and terns, and a huge shower of eggs would fall into

the sea. Then the visitors would land, and walk over the eggs and nests without

seeing them. On some islands you have to watch every step as the eggs blend

in colour with the surroundings; and on the pinnacles the nests are just a twist

of sea weed on the smallest of rock ledges. It is marvellous to watch the gillemots

fly and hover over the other birds with their little black webbed feet spread

out and squeeze themselves in to sit on their eggs, and all the time the noise

they are making must be heard to be believed. The watchmen live in the old castle,

very roughly, with a big open fireplace to cook on, and bunk beds. There is

a well on the island. Two of my brothers took it in turns to be on watch. One

of them, Fred, kept chickens there to study them, and wrote a book later called

"How to Make Poultry Pay". He used to fight (by letter) with the head

of the Board of Agriculture, and was grieved and hurt when the man died. My

other brother Edward, was nicknamed Jum. The name stayed with him throughout

his life. He used to go out to the islands in a small canvas canoe with a paddle;

it was so small the Seahouse fishermen said he was sure to be drowned.

Monks House must have been built on a rocky foundation, as the tide sometimes

came almost into the sitting room. Just sand, lovely silver sand and then sea.

We had two small white boats to hold 3 or 4 people; they were named after two

of my sisters, Lily and Olive. They were anchored high up on the beach, and

my brothers used to set a long line at night and haul it in next morning. We

set lobster pots as well. There was a buoy half a mile out to sea, and often

the catch was very heavy with cod, gurnet, flatties, conger-eels and puddlers.

I remember one year Bamburgh Castle being restored by Lord Armstrong, and about

20 wooden huts (houses) were built for the workmen and their wives. As we had

so many fish we though it a good idea to give them to these people. So with

our pony and trap we started out calling "Fresh Fish ", "Will

anyone have them"? At first no one answered, then word went round that

they were given, not sold, and out they came with dishes, and all were pleased.

Bamburgh Castle is well worth a visit, a lovely little village with two hotels,

and two boarding houses, a lovely golf course, and tennis courts. My sisters

used to go and play tennis most evenings. We knew so many of the people there,

and quite a lot like ourselves came North from Newcastle and London every year.

Seahouses has a good pier, and Scotch herring boats used to come down from Scotland

after the herrings, and the Cornish boats used to come there also. Sometimes

you could walk across the harbour from boat to boat, they were so tightly packed

together. The Cornish boats seemed to be the cleanest. One of them was called

the Alarum: we got to know the captain and crew very well, and they would take

my brothers out fishing at night. It was a pretty sight to see the fleet of

fishing boats going out with their soft brown velvety looking sails billowing

out. They would set their nets out at night and come in if the tide was right

in the early morning when the buyers would be waiting for them. Fisher girls

came down from Scotland to gut the fish, and they would be packed into barrels

and covered with salt, and sent all over. The Germans liked them a lot.

Mother felt the fishermen had nowhere to go except the 'Public House', so she

decided to rent a house overlooking the harbour, and put a caretaker in, and

provided note paper, newspapers and magazines, tea to drink, and there were

fires. I was not happy about this, as Mother had to write to friends and people,

to help to get the money to run it. She took lots of things out of Freelands

for this place. I do not think Father was consulted. Our billiard table went

there, and bookcases, chairs, and all sorts of things. I think she was the pioneer

of Fishermen's Clubs.

Grace Darling was the daughter of the Darlings and lived on the Longstone lighthouse

with her Father. One night during a fearful storm there was a shipwreck on the

next island, the Groundsman and the ship was sinking. It was such a wild storm

that Grace's Father could not man the boat alone. So Grace went with him and

they rowed to the wreck and saved the crew. She is noted in history for this

brave deed. She died very young of consumption and has a big tombstone in Bamburgh's

grave yard.

My eldest sister was married in Camburgh when we were staying at Monk's House.

I was about two, too young to remember. I am told I was nearly christened in

the little chapel on the Farne Isles, by one of my uncles on my Mothers side

who was a Parson.

The castle ruins on the Farne Isles used to be filled with beautiful oak carvings,

and the Ords who owned Monk's House had the dining room walls covered with these

carvings. The dining room was a very big room, and at one end there was a huge

oil painting of Jesus telling the disciples to cast their nets into the sea

again, and immediately the nets were filled with fish. I used to be spell-bound

by this picture. The nursery was a very long room and it had two double beds,

one of them held three people; also a small single bed. At the other end of

the room was a large round table and cupboard where we children had our suppers.

(There was a ship's bunk bed too). Large flat scones with few currants in them,

called half biscuits, and a currant loaf about half a yard long. I used to go

to sleep watching the Farne Island lights go in and out. We went about the sands

in old clothes and sand-shoes, or no shoes at all, and when we got back to Alnwick

we were as brown as gypsies.

We took our cow, horses and even hens to Monk's House. A big wagon came early

in the morning to pack all our belongings in. I can hear in my imagination now

the carthorse eating the hedge at the back door, and Tom Johnson, the driver

flirting with the maids. He had very blue eyes, and fair curly hair, and was

always asked to the maid's Christmas dance, which they had every year in our

big schoolroom. They were allowed to ask their friends.

We had a dance about every fortnight one winter. Mother made a good claret

cup with lemons in it; it was made in a huge high sided china bath, and was

ladled out with a soup ladle. Sandwiches, trifles and jellies were provided,

and a hunched back wee man who used to teach music and the violin, used to come

and play the violin while a friend of Mothers played the piano. The violinist

was called Geordie Robinson and was quite a bad tempered little man, and he

had, I remember, quite a tall dignified wife. All the same crowd came to these

dances. The Crisps, the Moors, Annie, Mary, the Dands, curates and bank clerks,

and school masters used to turn up. I was very young at the time, about 10 I

should think.

We were lucky in having this big schoolroom; sometimes it was a billiard room.

It had a stage at the end for plays, or charades, or ping-pong, or a laundry.

It had a lining of yellow varnished wood, and rafters of wood, with slates outside.

Two large windows and three doors leading out o to the garden. I remember when

it was a school we had a family of hedgehogs, and they used to try to nibble

our feet. A young squirrel was brought up there, and loved jumping from rafter

to rafter; I think we all got bitten by it. We used to have painting classes,

and lots of people used to come for these classes.

Mother was always trying to help people. One very hard winter she opened a

soup kitchen, and poor people would come and eat soup or cocoa, and they gave

counterfoils for it. Mother must have had these made, as I knew this was given

for these counterfoils, and not for money.

She started a laundry for orphan girls. The Duchess took this on, and made

the girls wear uniforms, which Mother thought was a shame. I do not know how

these things were financed. I knew little about money. As children we never

had any. On our birthdays and at Christmas, were the only times we had any.

I do remember though, being given a penny a dozen to catch snails. I found a

few old tree stumps that supplied quite a lot for my little hoard.

People used to give tennis parties, 6 or 8 people used to be asked, and a lovely

tea was always provided. I used to love these parties, and then whist drives

in the winter were popular, I loved them too. A whist drive in a private house

was really great fun; a glass of wine, coffee and sandwiches were the refreshments.

Sanger's circus used to come, and put the tents up in a field, we used to watch

the procession go through the town from my father's office windows. Often a

clown would walk on high stilts and look in at the window and wave. Then in

the evening we would go to the circus which was lit by flaring paraffin lamps.

The broad-backed white circus horses, the spangled lady standing on their backs,

and jumping through a hoop I thought marvellous.

We had a huge bonfire on Guy Fawkes Night, made with two old tar barrels, and

all the rubbish from the garden. And fireworks. My cousins brought fireworks,

and Father supplied quite a lot. I remember we had a cow that was very ill,

I think it was having a calf that would not come. A huge rocket and a big bang

roused the cow, and it raised itself, and soon got well again.

One night when coming home late from a party, there were most unearthly yells,

squawks and cries coming from the orchard. The pigs had got out, and they were

being chased by Tommy Train and some of the family with lanterns and sticks.

When I was young we did as we were told, I remember being put on the back of

a huge old-black horse and told to ride it down to Monk's House. I knew about

7 miles of the way, but I was hazy about the rest. I got the 7 miles all right,

and then old Jack stopped in front of a pub and refused to go on. I felt helpless:

if I got off I could never mount again; and then, to my joy, my sister Violet

and our cousin, came riding by on cycles, they whipped up old Jack and I was

on the road again. I recognized the way as I went along, but I was glad to get

safely there.

Our house had a flat roof in the middle, with slated sides going up. The snow

used to collect on the flat part, and drips came through the ceiling, so workmen

had to come to repair the roof, they had to go through a trap door from the

lavatory. In the evening someone in the garden said they saw smoke coming out

of the roof: it was on fire. A workman had left a lighted candle on a beam in

the attic which caught fire. The fire brigade was summoned, and my sister Winnie

filled buckets with water and helped to put the flame out. It was then discovered

that there was a secret room: a door way about 6 feet from the ground had been

papered over and when opened led into a small room, which became very useful

for keeping cases and old chairs and things in.

We had no bathroom in the house, but several rooms had a full sized bath in

a sort of cupboard: one in Father's dressing room, one in a spare room, and

one in a picture room, and a maids one under the stairs in the kitchen. I can

also remember in the large front bedroom a round hip bath being laid out with

big hot water cans and a mat on the floor. I have used a bath like this myself,

but much prefer our modern kind. Tommy Train used to clean all the shoes and

boots, and a huge wheel enclosed knife cleaner stood in this little room off

the pantry, and Tommy used to clean the knives.

There was a door from this room into an enclosed yard that had a dairy with

about six large shallow milk pans where the cows fresh milk was put, and a metal

sort of scoop to take the cream off. Next to this was the game larder, with

nails in the wall where pheasants, partridge, black-cock and rabbits hung in

their seasons waiting to be plucked and eaten. I used to like helping a young

kitchen maid to pluck the game while she told me fairy stories by candlelight.

I look back on my childhood as a very happy one, and I know I was one of the

very lucky ones. I was not spoilt, nor neglected; I had plenty of freedom, and

good health. Not having much in the way of looks or brains I was allowed to

choose my own friends. I had hardly any schooling, being too young for finishing

governesses. I went to a day school for about 2 years. I was always fond of

sketching, and at 14 went to Newcastle College to study Art, but only twice

taken out in class to sketch. I made some life-long friends there, but now they

have all passed on. I had a very happy marriage, and 3 really good children.

At present I have 9 grandchildren, and more on the way. What more can anyone

want?

Last updated 10 Aug 2016 - Olive's birth year corrected.

Updated 2 Jan 2008