"West Cornwall in the 1930s was a long way from London, and people still

had their own way of doing things. At Boskenna the tenants paid their rents

to the Colonel once a year and in person, after which he entertained them

to a raucous dinner. As time passed, his leases became more whimsical. They

might be granted on condition that the tenant had served in the army, or was

not a Roman Catholic (Camborne Paynter had no time for `Popery') or could

play bridge. Some of the most singular leases were granted to the colony of

artists the Colonel encouraged to settle on his land at Lamorna Cove, which

became a centre favoured by painters such as Laura Knight and Alfred Munnings,

and was well known to Stanley Spencer, Russell Flint, Ruskin Spear, Rodrigo

Moynihan, Henry Lamb and others.

Colonel Paynter's daughter Betty was once

reported to be engaged to Guglielmo Marconi, who had become one of her admirers

while working in West Cornwall on his celebrated radio transmitter. For some

reason the Colonel was irritated by this story and horsewhipped the pack of

newspaper reporters who gathered at Boskenna for the next meet of the Western

Hunt. He was an enthusiastic motorist but had little time for the Highway

Code. In the 1930s Betty also had a motor car, they were the only two drivers

in the neighbourhood, and they once met and collided at Boskenna Cross. The

Colonel alighted, instructed Betty to stay with the cars, walked home and

telephoned the police, telling them to arrest his daughter and charge her

with dangerous driving. He heard the case himself and imposed a driving ban

of several months. His own driving habits were notorious in the parish of

St Buryan and beyond. Once, as he sped down the lane, a terrified delivery

boy leaped off his bicycle and jumped into the ditch. `Foolish boy, foolish

boy,' said the Colonel as he flashed past. `I've nearly run him over once

already this morning.'

Boskenna was said to be full of ghosts. Mary's friend Pat Morris, who stayed

in the house in the 1940s, remembers it as being `very haunted' but not unpleasantly

so. `You just knew that everyone who had been there was walking about.' The

Colonel took the ghosts for granted. Once, when a guest complained that there

was a strange man sitting in a chair in the library, the Colonel said, `Get

Aukett to offer him a drink. That usually gets rid of him.' Aukett was George

Aukett, the butler, who had originally worked for the Colonel's grandfather.

Aukett played the violin at private recitals and `rendered popular ditties

with great sense of humour' according to The Cornishman.

Mary described Colonel Paynter as `an eccentric, hospitable and incredibly

tolerant father'. He in turn adored Mary and it was largely due to him that

Boskenna became her ideal house. The imaginary ideal house, or `great house

in the West', that appears repeatedly in her fiction, notably in The Camomile

Lawn, Not That Sort of Girl, A Dubious Legacy and Part

of the Furniture, was clearly inspired by Boskenna. It is typically a

house from which the sea can be heard breaking on the rocks at the foot of

the cliff, where an owl patrols the cliff path and where you lie in bed and

hear the cawing of rooks or the clatter of horses' hooves in the early morning,

or watch the firelight flickering on the bedroom ceiling late at night. The

fictional Henry, master of Cotteshaw in A Dubious Legacy, whose father had

enjoyed droit de seigneur in the neighbourhood, bears some resemblance to

the real-life Paynters of Boskenna, whose distinctive features were said to

crop up regularly among the children of St Buryan. In extreme old age Alice

Grenfell happily recalled the time when as a young girl she had received her

first wages from the Colonel and he had smiled at her and said, `You belong

to me now, Alice.'

The Colonel's tolerance was partly due to the fact that Betty's mother had

died in February 1933, after which the house lacked any conventional governing

influence. The extra-legal funeral arrangements made for Mrs Paynter were

very much in character. She was said to have died after a short illness. In

any event, as one friend of the family put it, `They didn't get on.' No undertaker

was involved since the Colonel had his wife's body taken to St Buryan church

on the back of the estate lorry. The coffin was plain oak with iron handles.

After the funeral service the coffin was taken back to the Boskenna estate

and Mrs Paynter was supposedly buried with her dog at her feet in a private

grave on the cliffs between her Japanese garden and a flower farm. Others

remember a service on the rocks below the cliff, where the Colonel scattered

his wife's ashes into the sea and then turned to the mourners, rubbed his

hands and said, `Well, that's that. Now who's for a game of bridge?' There

was no inquest.

His wife gone, the Colonel, whether through grief or high spirits, dedicated

himself to a second youth. He spoke French, Italian, German and several other

languages, and his daughter Betty was encouraged to make Boskenna the centre

of a cosmopolitan circle of friends, young people from London who were looked

on unfavourably by those who were trying to keep the estate going. Mary described

it as `an entirely new set of people, sophisticated demi-monde'. A new neighbour,

Wylmay Le Grice, was taken by her husband to visit the Paynters and donned

twin-set and pearls for the occasion. They rang the doorbell of Boskenna and

after a long wait the door was flung open by a statuesque and naked young

lady who said, `How-do you do? I'm Paula.' The Colonel had brought her down

for the weekend, from the Windmill Theatre in London."

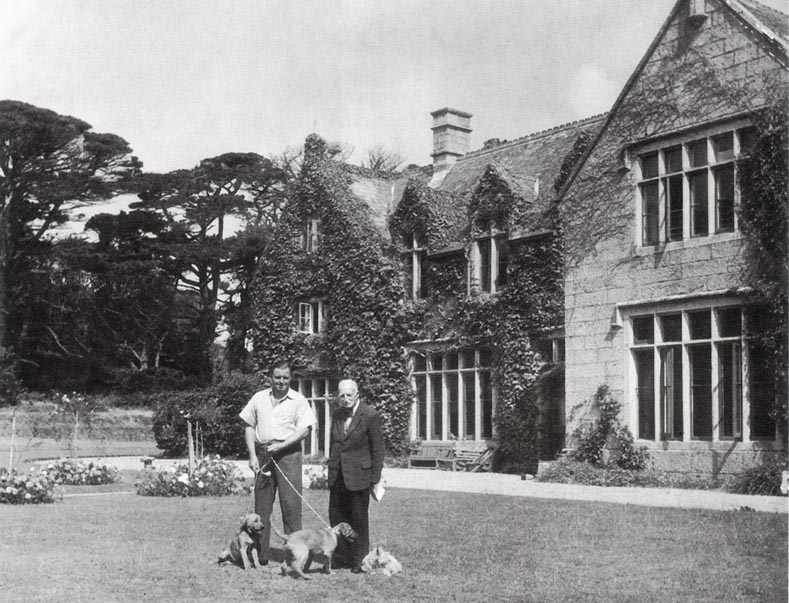

Col Paynter (right) in the garden of Boskenna circa

1946